"Qi" - calligraphy by Zhu Tiancai

I recently followed the comments of a long time Taijiquan player on the internet. He was decrying the dilution of the traditional art and came to the conclusion that this was the fault of the current generation of silk-suited believers in "Qi". Was he right? Is Qi no more than an interesting historical concept of little relevance to today's Taiji boxer? Or is it a central concept that must be understood if we are to understand the art of Taijiquan as it has been passed down?

Chen Xiaoxing stated that it is impossible to reach a high level of Taijiquan without having a deep understanding of Chinese culture. "Students can reach a low level by copying the movements, but they could never hope to realise the depth and subtlety of Taijiquan without this understanding".

One of the most pervasive ideas within Chinese culture is the ever presence of Qi. At the same time, many western practitioners are extremely sceptical of its existence, dismissing it as an antiquated idea - knowingly pointing to the lack of "scientific" evidence? After all, they argue, it can't be seen, measured, touched etc...

To the Chinese the idea that there is no such thing as Qi is just as ridiculous. To them Qi is an ever-present feature of life. Within the Great Dictionary of Chinese Characters, a vast compendium of Chinese characters spanning 8 volumes, no fewer than 23 different categories of Qi are listed. Categories such as: mood, morale, weather, energy, structure, vapour, momentum, destiny, spirit, meteorological phenomenon, atmosphere, strength, destiny, breath, smells... Within each category again, there are numerous different types of Qi.

To people who say that you cannot see or measure Qi, I would suggest they are looking in the wrong place. It has always been said that while Qi itself cannot be seen, it's effects can be felt. Doesn't it feel different to be fully energised than to be depressed? The Chinese use the expression Shen Qi to describe a state of heightened energy, self-confidence and pride (in the positive sense). Look at someone who has just won an Olympic gold medal or scored the winning goal in the dying seconds of an important football game. Compare the feelings they have with those of someone lacking drive and self-belief.

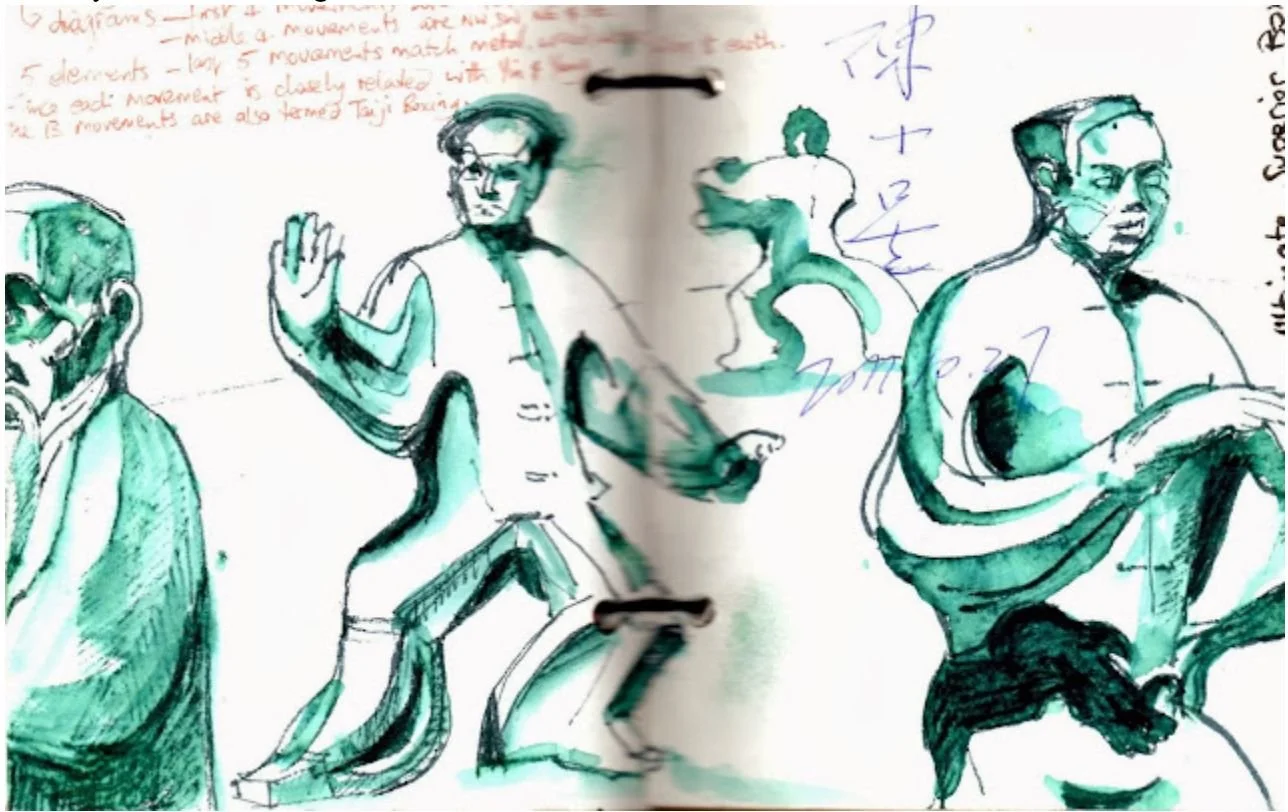

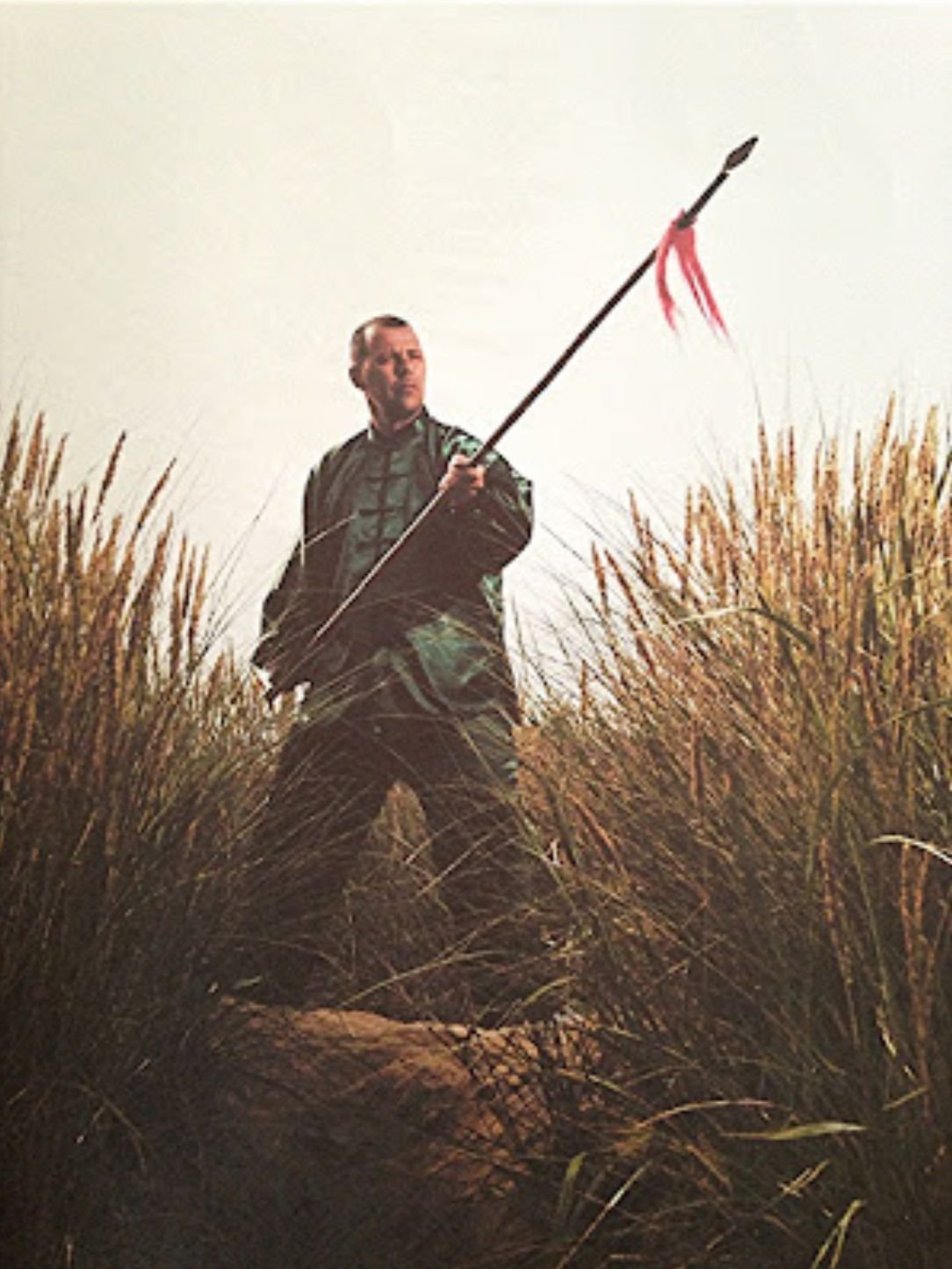

Another way in which Qi is understood within Chinese culture is in terms of momentum. In literature, art or martial arts mastery is achieved when a movement is completed in one swoop with no hesitation. When I started training Taijiquan one of the main differences I became aware of between the good practitioners and the majority of western practitioners was a kind of inhibited way of doing Taijiquan. As if they were constantly afraid of making a mistake.

In literature, arts or martial arts, mastery is achieved when movement is achieved with no hesitation. Image: Janet Grimes

After twenty years of training they still stop every movement put their hands on their coccyx to physically check that they are in the right position. Don't get me wrong - Taijiquan requires constant rigorous attention to detail. But it also requires that a practitioner should exhibit spontaneity, fluidity and naturalness. At some point you have to start FEELING whether the position is correct. In an earlier blog post I wrote of Chen Xiaowang's response to the question of differences between Western and Chinese students. In his opinion one of the major differences was that Western students paid more attention to the external position and Chinese students paid more attention to the feeling of the movement.

Students often spend so much time agonising about Qi and trying to understand it in terms of their own culture which inevitably leads to approximations and misinterpretations. [FIRST PUBLISHED 10/12/2013{